The Benefactors invite you to become a friend of

The House of Apache Fires

The historic Frye Home built in the 1940s on their ranch is now one of the gems of the park. But rain and wind have caused considerable damage to the roof and interior. The roof has been replaced by a joint effort between the Benefactors and AZ State Park. A joint committee and now determining the next steps in the project. We are hopeful that this Pueblo revival house can be opened for tours in 2022. Learn more

Roof repair and building stabilization are complete, further improvements will depend on donations. Donate now

History of

The House of Apache Fires

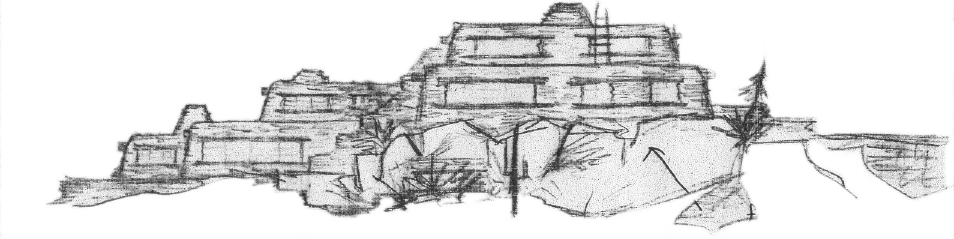

There have been many hopes and dreams for the House of Apache Fire but none have ever been fully realized. It was to be Jack and Helen Frye’s dream home. When the Fryes acquired the 700 acres (about 1 square mile) along Oak Creek outside Sedona from four homesteaders in 1941, they already owned 50,000 acres in the Southwest where they raised steer. However, it was at their Oak Creek property, where they began to conceptualize The House of Apache Fires, a pueblo-styled home on a bluff with an architect from New Mexico, John Meem, who was influential in championing the adobe style of architecture in Santa Fe. They conferred over five years; a preliminary plan evolved into an 11,610 square foot house at an estimated cost of over $120,000 in November 1946. The correspondence between the architect and Helen Frye over those years was exhaustive. No detail was too small. About the master bathroom, she wrote, “I would like the mirrors on the cliffside so that they may be turned in any direction….I want a small compact folding desk built in the walls by each toilet with a space for a few books, writing paper, etc. I also want a satisfactory reading light for this location.”

Because of World War II, they could not start construction until the fall of 1947. Jack Frye was alarmed by the cost estimates as presented by Mr. Meem and so from these preliminary drawings, the house was pared down to about 3,000 square feet to cut costs. To pay for the construction, which lasted over two years, they sold what is now known as Cross Creek Ranch at a price more than what they had paid for the property.

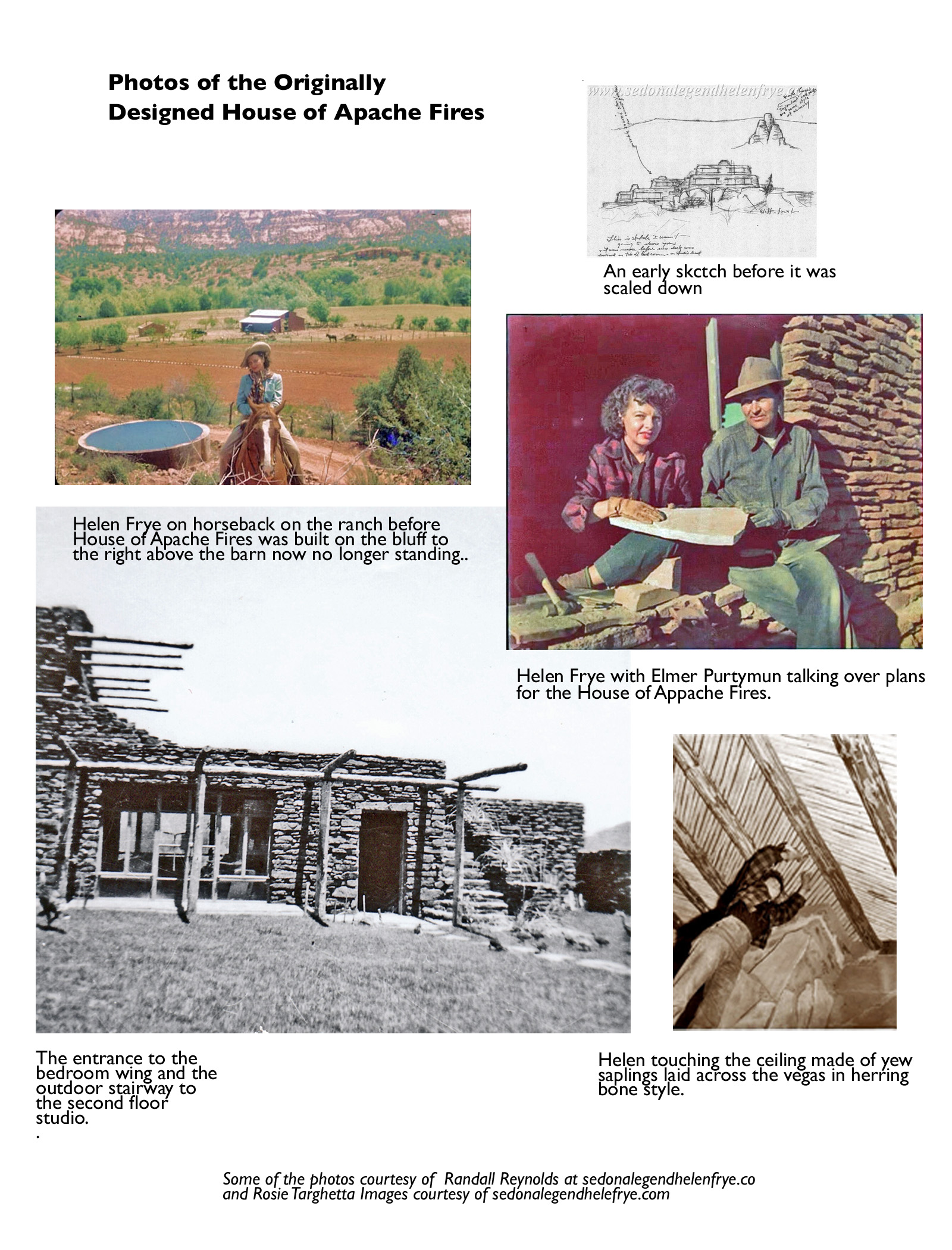

With the revised plans they used a local contractor, Elmer Purtymun, and labor procured primarily from the nearby Yavapai/Apache tribe and Hopis. Although the Fryes built a bunkhouse near the well for workers during the construction phase, the Apaches, who comprised much of the labor force along with Hopis, preferred to camp by the river to keep cool. When Helen Frye looked down and saw all their small fires by the riverbank she decided to name the house to be, House of Apache Fires.

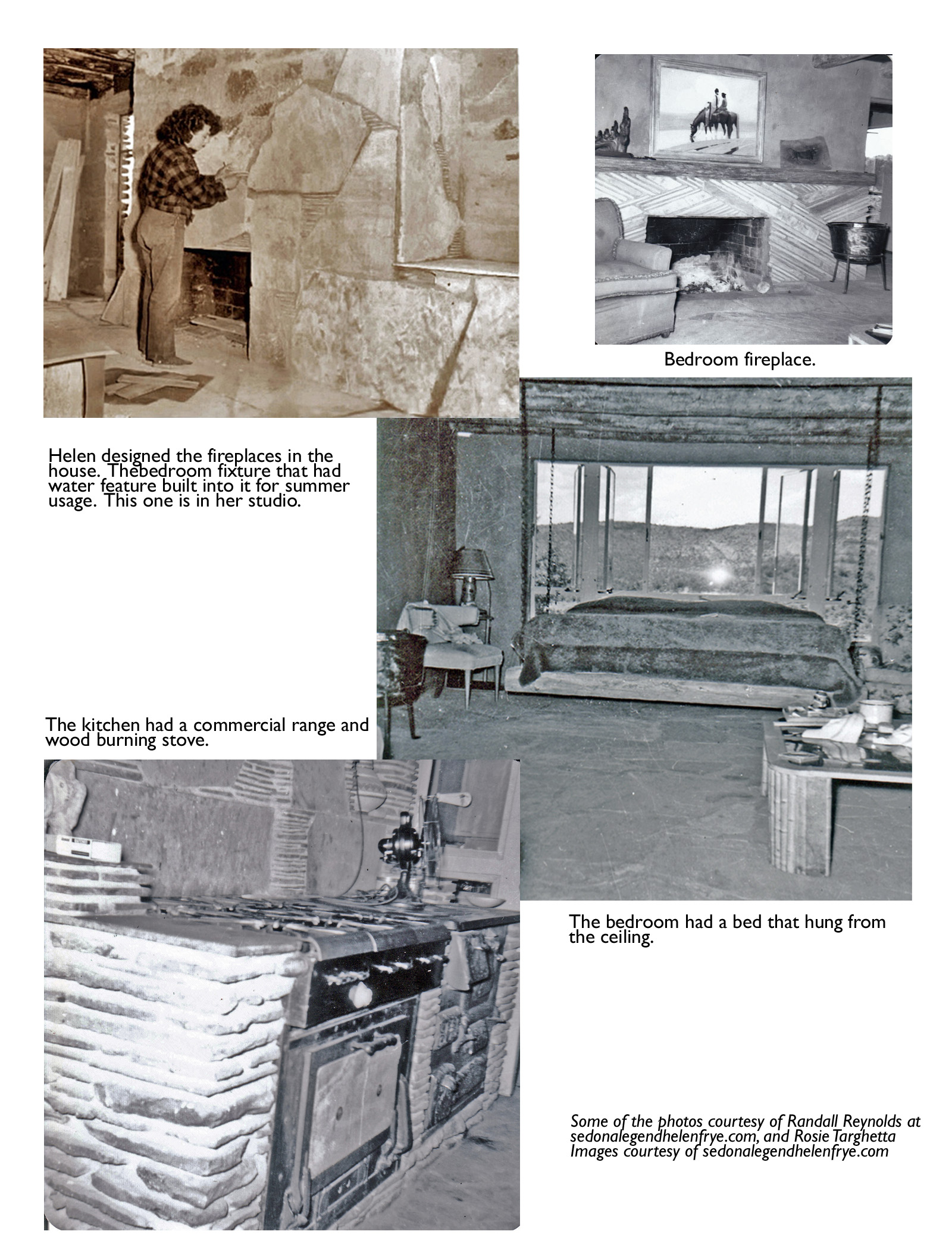

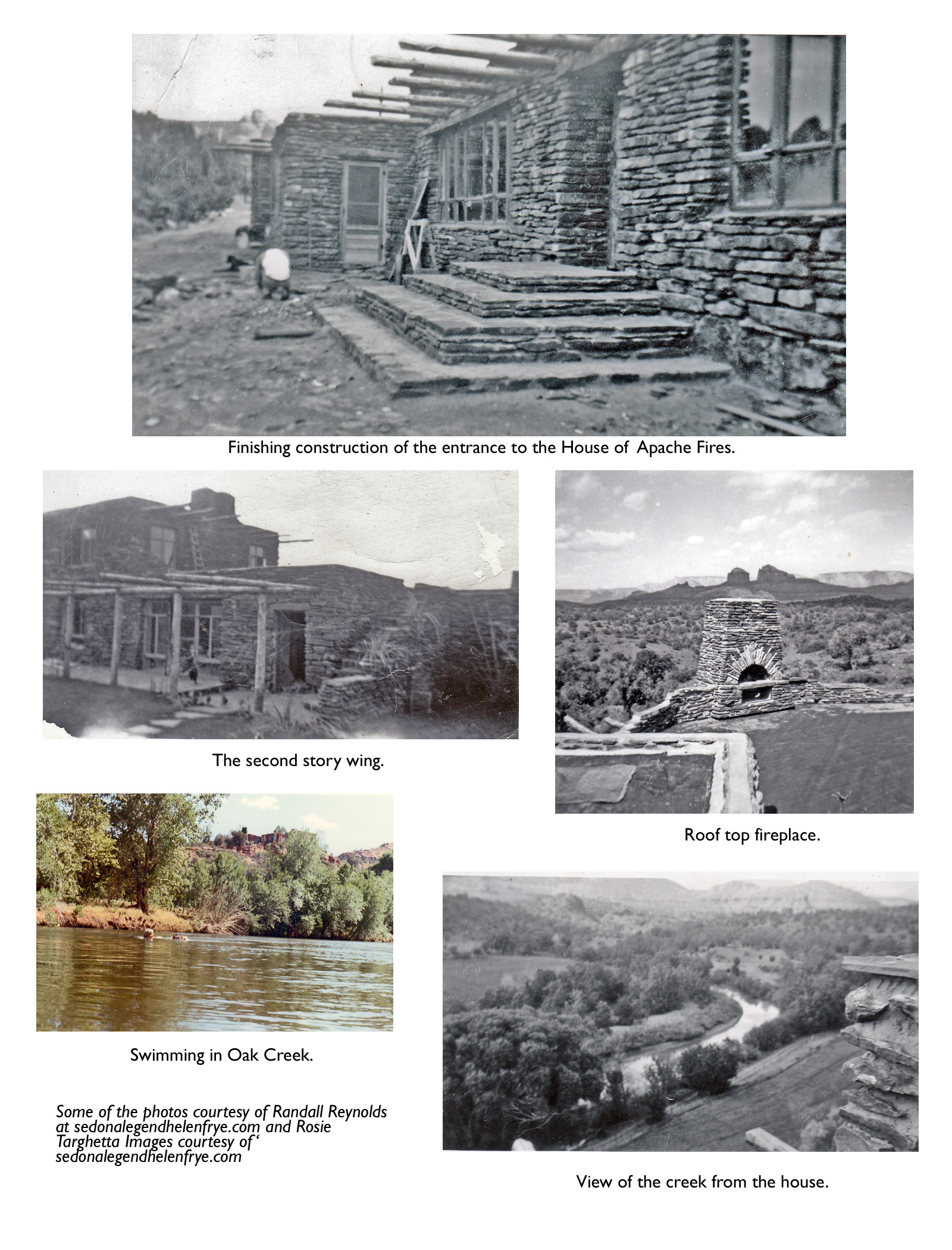

They put in vigas (beams) using wood from Flagstaff. Ceilings were fashioned from yew saplings laid across the vigas in herringbone style. Floors were made of flagstone from Cottonwood and travertine Buckeye limestone. The walls were made of rough plaster painted in shades of sand and brown accented with turquoise. The bedroom had a hanging bed and a fireplace that could be converted to a water-reflecting pool in summer. The kitchen had a commercial range and a color combination of copper, pink and turquoise with cupboards painted in a Zuni design. A stone mural was placed above the stove. All of the fireplaces had a unique design fashioned by Helen Frye.

As construction began their life together changed drastically. Jack Frye was forced to resign from TransWorldAirlines in February 1947 over a dispute with Howard Hughes after 13 years as its president. Soon afterward he became president of General Aniline and Film Corporation, a competitor of Kodak, and had to spend much time on the East Coast. The Fryes divorced in June 1950 about the time house construction was completed. Jack soon married a showgirl, Emily Nevada Smith. In the divorce settlement, Helen Frye became the sole owner of Smoke Trail Ranch and the House of Apache Fires with alimony for four years. There was an attempt at reconciliation with Helen in 1958 after Jack resigned from Analine to start an aircraft manufacturing company in Tucson. He was contemplating divorce from Nevada Smith but died in an untimely auto crash in February 1959.

During the three years of construction, Helen had experiences that shaped her beliefs about healing and the sacredness of the land on which she lived. She had a fall from a horse that left her humerus bone broken with nerve damage. In spite of an extensive cast taken off and on over 6 months, there was no healing. She decided to take matters into her own hands by bathing in Oak Creek in an attempt to heal her hyper-extended arm. Much to the surprise of her doctors, she regained use of the arm. She found that the creek water also healed rope burns. An even more vivid experience occurred with a rattlesnake that threatened just inches away. After several anxious moments, the snake stopped rattling and slithered away over her foot. When she consulted with a Native American healer about her experiences he convinced her that she lived on sacred healing grounds. In spite of an earlier history of rifle hunting, she vowed to kill not even an insect such became her reverence for all forms of life. She developed an interest in mysticism. At around this time, a tutuveni rock (Hopi writing rock) was discovered on the property, bearing clan symbols of Hopi ancestors prior to 1040 AD on the property. A Hopi elder explained that it meant that this was a place where all future tribes would gather to create peace and harmony.

In the 1950s the Sedona community numbered about 500 people whose lives were intertwined with the arts, movie making, and an interest in spirituality. The Verde Valley School, 2 miles away from Smoke Trail Ranch, was established in 1947 by Hamilton Warren, a New Englander. It became the school that often enrolled the offspring of movie stars who resided in Sedona while a movie was shot on location. The school became the social hub for its neighbors as well as the movie stars. Tyrone Power was a frequent guest of Helen at her house.

Hamilton Warren’s mother recommended that her son hire an Egyptian sculptor and architect, Nassan Gobran, as the art director for the school. She had known him as the set designer of the Berkshire Music Festival at Tanglewood in the summer of 1949, a job he took after his graduation from the Boston Museum School. When he arrived in Sedona in 1950 he was overwhelmed with the scenery and began to envision how Sedona could become a “Tanglewood for the Arts.” In 1954 he formed a relationship with Helen Frye to help her prepare and sell land at what is now known as Cup of Gold where he also designed a few of the houses until 1964. He and Helen became lovers, albeit querulous, for many years. They soon embarked on a plan to turn House of Apache Fires into an art center and group living home. In 1957 she sold him the house and ten acres for $8,000 with the provision that she has access to the second-floor studio to paint. Nassan planned to use the house to teach Verde Valley School students and host Hopi artists. It is unclear what eventually materialized. He had responsibility for maintaining and improving the first floor by putting in new windows, some wood flooring, a 600-foot well, leech fields, and heating. He needed financial backers to accomplish all this but reached an impasse with Helen Frye in 1961. She insisted that this be not only an art center but also a center for the study of UFOs and metaphysics. The backers refused. He eventually sued Helen to recapture the money he had spent on improvements.

By 1957 Gobran had also gathered a group of artists and supporters to form Canyon Kiva, which later became the Sedona Art Center. In 1961 supporters eventually bought the Jordan Orchard Barn to start the Center, which was initiated by Guy Lombardo and his band with the audience in the shed and outdoors. It is said that Helen Frye suggested the site for the Center.

By 1962 Helen Frye had built Wings of the Wind house on the 32-acre plot looking down on the Smoke Trail Ranch. Not a part of the original ranch purchase, Jack Frye had earlier traded land with the Forest Service for the acreage. She may have had a prior plan for this house to be built atop Eagles Nest since in 1958 she took out a permit to dynamite the site for construction. She began a relationship with Ted Henning who as her mentor helped her channel reincarnation life experiences in which she relived the life of an Incan girl who was given a plan to save their civilization. At another time she had been given a plan that had originated in Atlantis before the inhabitants were evacuated to the Yucatan. This plan for a world peace government she thought was now hidden deep in the jungle there. She continued to explore such a phenomenon later in her life.

A 1967 snowstorm caused major roof damage to the House of Apache Fires destroying some of the interiors. That same year a Walt Disney film, Legend of the Boy and the Eagle was filmed using House of Apache Fires as a Hopi Village. The story is based on a legend told by one of Helen Frye’s many Hopi friends, White Bear, who played the part of a shaman in the movie and worked part-time at the Verde Valley School.

Later, in 1968 she joined the religious sect Eckankar with whom she studied, and became a priestess. She attributes having gained control of her smoking and drinking habits to Paul Twitchell, who founded the cult in 1965 as a westernized version of yoga practices from India that places an emphasis on soul transcendence. Interest in spirituality was common among some of the residents of the Loop Road area. Her neighbor, Lois Kellogg Duncan, had an ashram on her Crescent Moon Ranch about one mile away. Another neighbor interested in Hinduism and Buddhism, Mary Lou Keller, founded the Sedona Church of the Light near where Hillside Mall now resides. It became a place to welcome psychic healers of all persuasions. She was the one who introduced Helen Frye to the Eckankar group who held beliefs in reincarnation, karma, and out-of-body-travel in dream states.

Later, in 1968 she joined the religious sect Eckankar with whom she studied, and became a priestess. She attributes having gained control of her smoking and drinking habits to Paul Twitchell, who founded the cult in 1965 as a westernized version of yoga practices from India that places an emphasis on soul transcendence. Interest in spirituality was common among some of the residents of the Loop Road area. Her neighbor, Lois Kellogg Duncan, had an ashram on her Crescent Moon Ranch about one mile away. Another neighbor interested in Hinduism and Buddhism, Mary Lou Keller, founded the Sedona Church of the Light near where Hillside Mall now resides. It became a place to welcome psychic healers of all persuasions. She was the one who introduced Helen Frye to the Eckankar group who held beliefs in reincarnation, karma, and out-of-body-travel in dream states.

By 1973 Helen Frye had sold the 306 acres of the Smoke Trail Ranch to a development company that wanted to build a “Resort on Oak Creek.” After three years the development company failed. And Helen proceeded to find a way to rescue the property. In February 1976 she gave the 32 acres on which she had built Wings of the Wind house to Eckankar as a “gift deed” with the provision that she have life-long occupancy rights and that they develop the property as a spiritual center. In August of 1976, she also gave Eckankar $800,000 to purchase The Smoke Trail Ranch from the defunct development corporation with the understanding that Eckankar would add an additional $400,000 and accept a provision that put restrictions on development. She also gave large sums of money to help with renovation costs to the Apache House of Fires that was to become a retreat center, called the Eckankar Blue Star Spiritual Training Center. Eckankar revamped the dressing rooms and made public bathrooms in the far wing, added new doors and mirrored windows. A Jacuzzi was installed on the second floor. They put down wood flooring in the living room and dining room by using dirt fill between wood struts placed over the original stone to make the wood floor on the top firm and to possibly provide insulation. The roof was once again repaired.

Three years later in July 1979, a public rift within Eckankar began. It was rumored that the group would sell the property and not fully continue the spiritual commitment they had promised. They were lacking sufficient funds and the leadership team was divided about what next to do. They refused Helen Frye’s offer to buy the property back. The organization seemed to be unraveling. Some of their sacred documents were missing. Tom Charly Wallace, the young Eckankar member who lived with Helen Frye for several years and was her business manager and lover, broke with the group years before.

By June of 1979, Helen Frye discovered she had terminal cancer. She is said to have torn up her will in her displeasure with the Eckankar group and moved for a time to the home of a close neighbor, near to a house she never completed building in the Village of Oak Creek (which burned to the ground in 1983). In September she complained that Mr. Wallace had lied to her and ordered him out of the house for a time. However, when she died on December 4th at the Wings of the Wind house, she was tended to by Mr. Wallace, her sister Mildred, a niece, and Rosie (Targjetta) Armijo. Rosie had known Helen for over 30 years. She was the 16-year-old sister of the ranch foreman and became her housekeeper when she broke her arm in a horse ride accident. After high school and while in college and later working, Rosie often visited Helen. Adopted as her surrogate daughter, their friendship continued after Rosie married and moved to Santa Fe.

Eckankar forcefully evicted Wallace from Wings of the Wind on New Years’ Eve 1979 and subsequently, the group stole several items from the house. They never found the original will. The scandal became public in a jury trial in 1981 when the will was disputed in court over the remains of her assets (but not the property). No original will was discovered, only the carbon copy presented by Eckankar. The court was told that Helen Frye had torn up the will over her displeasure with the group. Other evidence was entered in the court proceedings when Charly Wallace testified that he had been bribed to give favorable testimony to Eckankar, which he documented with recordings of two telephone conversations. The jury ruled in favor of Helen Frye’s twin sisters. The proceeds whose estimated worth of $500,000 were later divided among her sisters and Mr. Wallace.

The Eckankar group had had a plan in late November 1980 to build twelve housing units for 96 Ekists and talked with the University of Arizona to use the part of the ranch for range and livestock research. Although the neighbors were skeptical, the Yavapai Planning and Zoning Commission gave conditional use approval. The matter came to a quick conclusion when Governor Babbitt intervened. In 1980 he was hiking with friends along Oak Creek when an Eckankar associate confronted him and asked him to leave since he was trespassing. Governor Babbitt had a life-long devotion to this Sedona property that his family had often visited with his Uncle George Babbitt, who owned a cabin in Oak Creek Canyon. He subsequently arranged for the Anamax Mining Company to buy the 286 acres (Smoke Trail Ranch) in exchange for an equivalently valued property the state-owned in southern Arizona suitable for their mining interest. This required legislative approval. In 1981 the land was bought from Eckankar and after a complicated process, Red Rock State Park became steward of the House of Apache Fires. Later In 1993 Wings of the Wind and all of its acreage was sold to a development company.

Work has begun to repair the house. Several years ago a windstorm lifted a portion of a patio roof on top of the studio rooftop causing leaks that have greatly damaged the interior. Debris has been removed. The stone floors are in the process of being cleaned and reclaimed. Funds are being raised to fix the roof. We hope you will join this effort. We are now in the position of the many that have come before us. Can we realize the full potential of the House of Apache Fire: A historical architectural gem, an arts venue, a conference center, a performance site?

Sam Braun (Draft 12/9/16)

Acknowledgments

A major source for this history is indebted to Randall Reynolds who has preserved photos, home movies, and documents for his website: sedonalegendhelenfrye.com. Some of the photos and movies are attributed to Rosie Armijo Targhetta Images and Varner Images courtesy of sedonalegendhelenfrye.com. The home movies of the Fryes and their ranch (a portion of which is now Red Rock State Park) have been edited by Randall Reynolds in several parts and are available on YouTube and his website. The John Gaw Meem Archive at the University of New Mexico is copy-written and contributed by Randall Reynolds through Sedonalegendhelenfrye.com. Mr. Reynolds has also written a novel, Jack & Helen Frye Story: The Camelot Years of TWA, (2015, CreateSpace).

Numerous newspaper articles, photos, and documents were available through the courtesy of the Sedona Public Library, the Sedona Historical Society, and files kept by the Red Rock State Park. The Red Rock News was responsible for many of those articles about Helen Frye, Nassan Gobran, Eckankar, and the Frye ranch.

Several people have shared memories about the House of Apache Fires or Helen Frye: Mille Leenhouts, Maggie Perkins, Joy Salzman, Jeffrey Perkins, Paula Zutz Duncan, Lyman Brainerd, and Tom Appleton.

Much of the information presented on this page are from stories that the narrator has transcribed. True oral history is a method of conducting historical research through recorded interviews between a narrator with personal experience of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer to add to the historical record. Because it is a primary source, oral history is not intended to present a final, verified, or “objective” narrative of events or a comprehensive history of a place, such as the House of Apache Fires. Instead, it is a spoken account and reflects the personal opinion offered by the narrator, and as such, it is subjective.